My note-taking process

I love being efficient and there is nothing like a feeling of wholesomeness at the end of the day when you realize that you have not wasted it. I am not incredibly productive, but I am more productive then some people, including myself for practically my whole previous life.

I attribute my recent increase of productivity to my knowledge acquisition system. It is not a perfect system indeed, and always a work-in-progress, but it stuck with me for months now, which is a good sign. Additionally, it has ordered my life, eliminated much friction and helped systematize all my intellectual activities. Maybe this post will inspire you to create a similar system, or improve yours.

Overview

The main components of my system are:

- Zettelkasten, stored in a git repository and organized in Emacs with

org-modeandorg-roam. - Book storage: cloud storage with digital articles and books, and a bookshelf with physical books.

- An Android tablet with a stylus to keep a working set of documents and annotate them.

- An e-ink reader, which mirrors a part of my collection of books.

The main stages of my workflow are:

- Reading/watching and making notes as I go.

- Revising, copying notes to my long-term note storage.

Now, to the details.

Data flow

Most of the time, I study by reading books, articles, and blog posts. Watching videos is less convenient, but sometimes I have no choice. I will illustrate the workflow on an example of a physical book.

Introduction to the source

First, I need to get a general idea of what is happening in the book. Linear reading is inconvenient for the task, so we need to approach the text structurally.

To begin, I am looking at the table of contents, skimming through pages, reading the section headers, sometimes section introductions. It is enjoyable doing this with a physical book!

Often, the book is either not entirely new for me, or only some chapters are useful — it is necessary to identify them before reading. This is most important if the book is not an easy reading: sometimes, getting through every single page may require an extensive research and an exhausting thinking.

My goals at this stage are:

- Familiarize myself with the book structure.

- Ask Google/ChatGPT about the meaning of unknown technical terms.

- Identify my goals in reading this specific book.

- Think for a moment about the questions that appear in my head after skimming through the book.

Some books are going an extra mile to guide the reader, for example, "The Network State" starts with sections "The book in one sentence", "The book in one image", "The book in one thousand words", and "The book in one essay". This is a didactic approach that I am also using with my students: guide to ideas through a series of increasingly detailed approximations.

Annotating the source

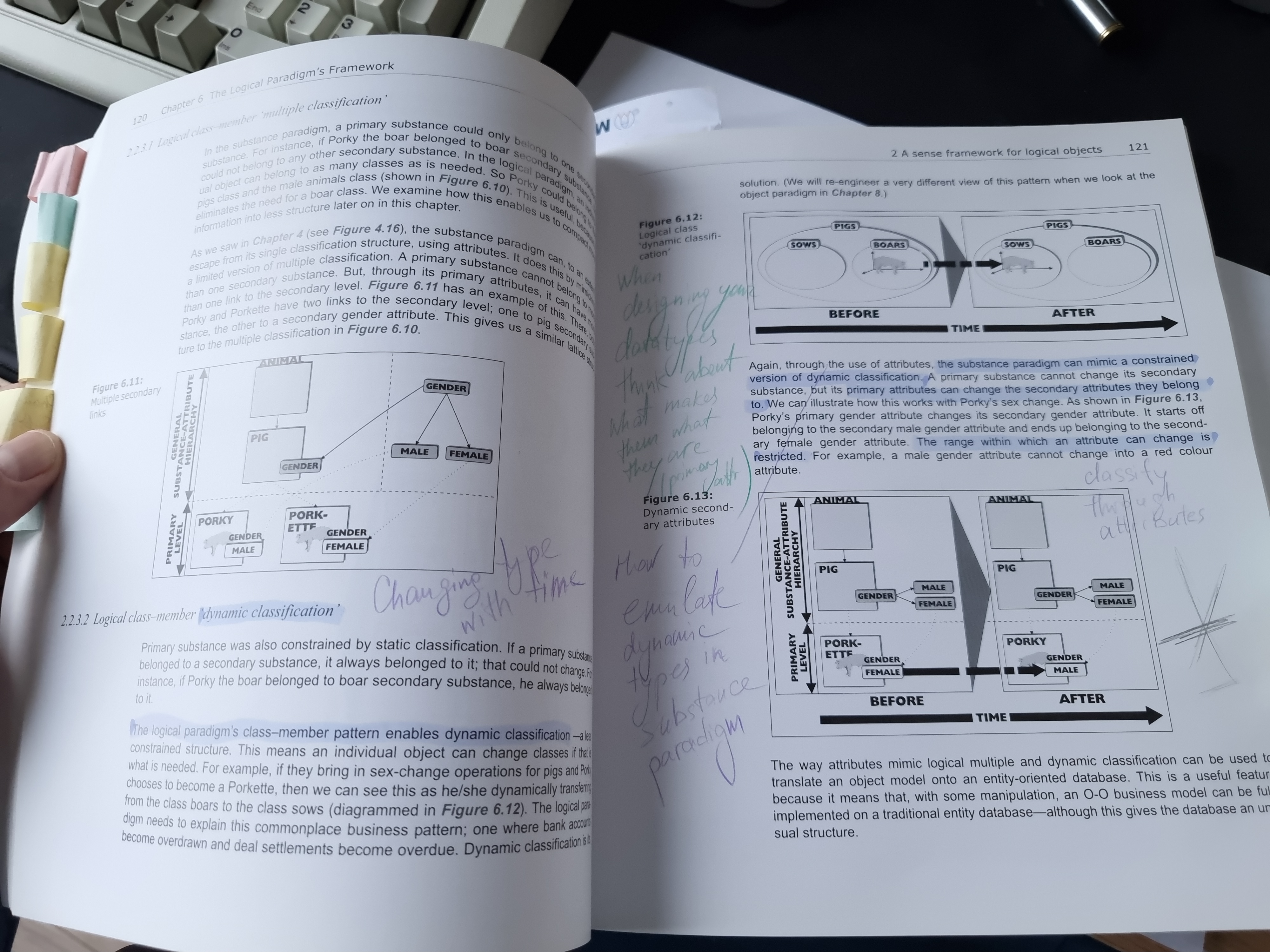

Once I have a general idea of what to expect from the book, I start reading and annotating it. As a kid, I was reading fast but memorized little, so now if I am serious about working through the text, I am annotating it. I use a set of four pencils and four highlighters of colors: violet, blue, red, and green. When something picks my interest, I highlight a fragment of text with one of these colors and write text on margins in the same color. This way a commentary is matched to a fragment.

There is a logic to my color selection:

Violet is for summarizing. It is well visible on paper and also distinguishable from black, so it does not fuse with the text.

It is not useful to highlight without commenting. Writing summary is mandatory, highlighting is optional 1.

- Blue is for connections. It reminds me of hyperlinks on Web pages. With blue I mark reasonable connections to other topics, writers, or books. Connections greatly enhance retention.

- Red is for questions and critique. It attracts the most attention and is associated with danger. I use it if I do not agree with the author, or if I do not understand a fragment.

- Green is for everything else. It is a safe, a bit disconnected color. If my curiosity suggests me a possible connection to my previous readings, if I get an idea on how to solve some problem, an analogy, a metaphor, then it is worth noting it. Basically, this is the color for everything else.

I am never waiting to finish one book before starting another, so my working set of sources is usually large. Reading many books on the same topic helps establishing more connections. Sometimes, it also enhances understanding, since I am exposed to several explanations of the same concepts, often from different points of view.

Every now and then I revise the notes to add information to my permanent note storage.

Storing notes

The core of my system is Zettelkasten. It is a personal Wiki with small subjective articles and annotated subjective connections between them. Each "wiki article" is a note on something: a concept, an idea, a book, an article etc. After some reading, it is time to revise my notes, skim through the book again, and put the bits of notes into the appropriate notes in Zettelkasten.

I like taking notes in two stages:

- It forces me to come back to notes in a systemic way. I re-read, re-discover things that I missed, and memorize information better.

- It combines the advantages of hand-writing and digital note-taking.

- Handwriting is good for retention; sheets are more "personal", it stimulates thinking.

- Digital note-taking is fast, notes are easier to systematize, much easier to edit and illustrate, they can benefit from the version control systems etc.

I use emacs with org-roam to keep my Zettelkasten organized, easily search through them and

explore them with org-roam-ui.

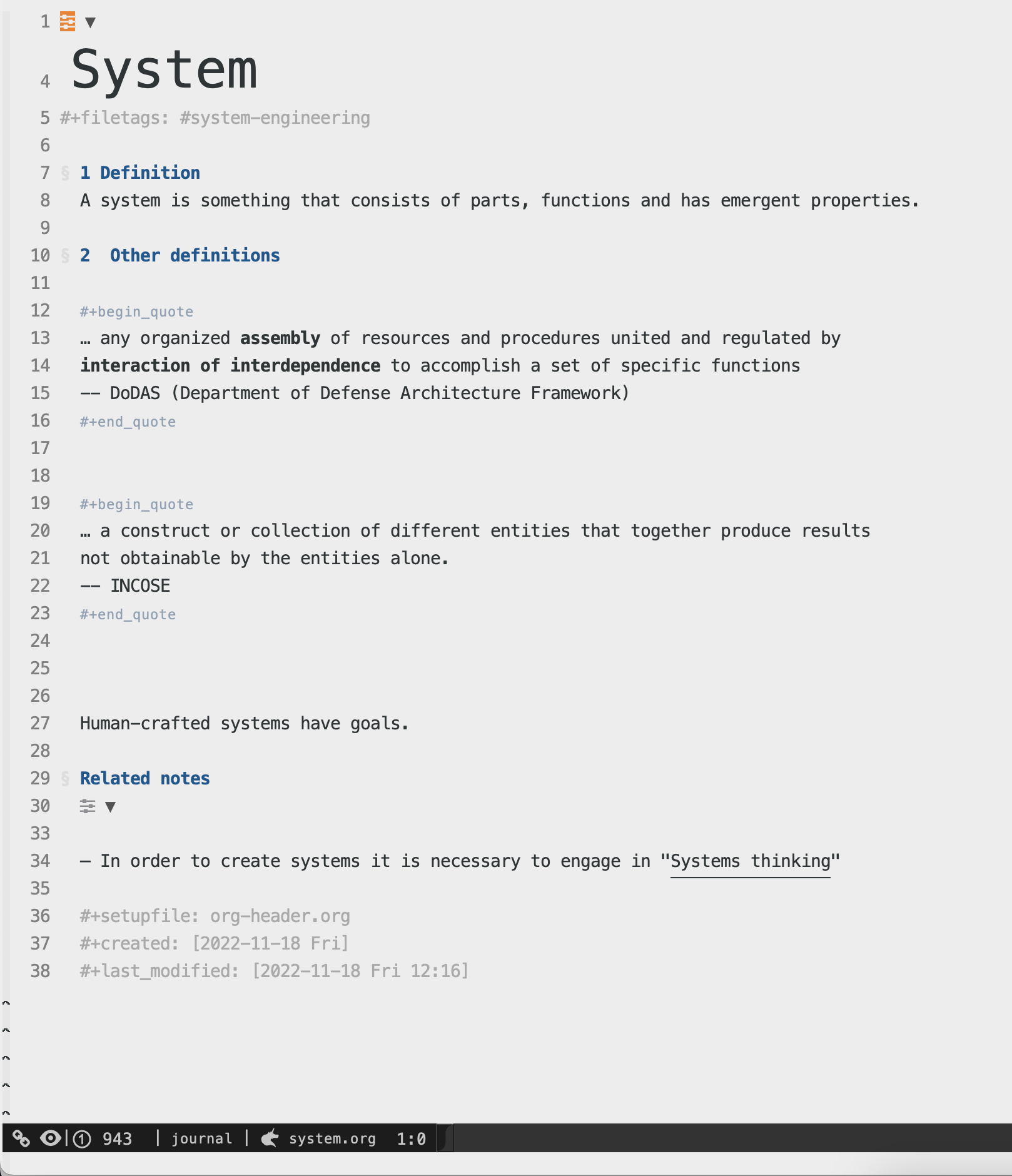

Here is an example of a note:

… and its source code:

:PROPERTIES: :ID: 22AF419C-C79F-42A6-B7E9-CF7A27DAD5E0 :END: title: System ▼ Definition A system is something that consists of parts, functions and has emergent properties. ▼ Other definitions quote \dots any organized *assembly* of resources and procedures united and regulated by *interaction of interdependence* to accomplish a set of specific functions -- DoDAS (Department of Defense Architecture Framework) quote quote \dots a construct or collection of different entities that together produce results not obtainable by the entities alone. -- INCOSE quote Human-crafted systems have goals. ▼ Related – In order to create systems it is necessary to engage in "Systems thinking" 2022-11-18 Fri 2022-11-18 Fri 12:16

The note contains:

An identifier for

org-roam(generated automatically):PROPERTIES: :ID: 22AF419C-C79F-42A6-B7E9-CF7A27DAD5E0 :END:

- Title

- Tags (we can then search by them)

- Sections with content. Text supports markup: underline/bold/italic,

monospace, strike-through and alike; it may contain pictures (there is a

convenient way of including shot of a part of the screen through

org-download-screenshot). - A special section for connections to other notes Personally, I am also putting links to other notes directly into the body of the note. The special section is precious to provide subjective annotations for the links: why do I think there is a connection between this note and another one.

I used to have two sections: for links to the sources, and for related notes, but now I tend to just merge both into "Related".

I keep most metadata out of the way by putting it in the end of the note.

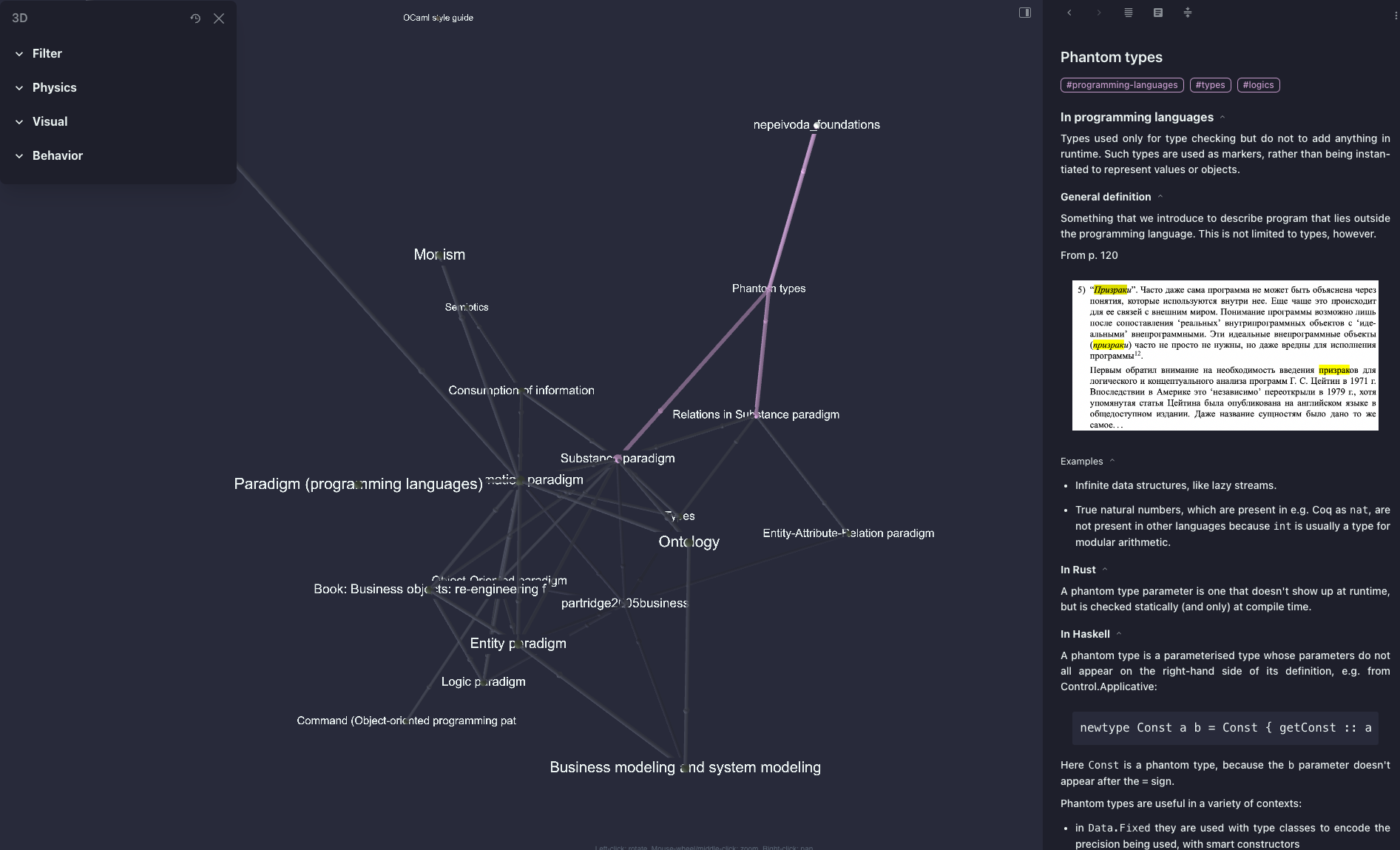

Additionally, emacs lets us explore the connected graph of notes in 3D, filter

them by tags, preview them nicely etc. thanks to org-roam-ui.

It looks like this:

What about digital sources?

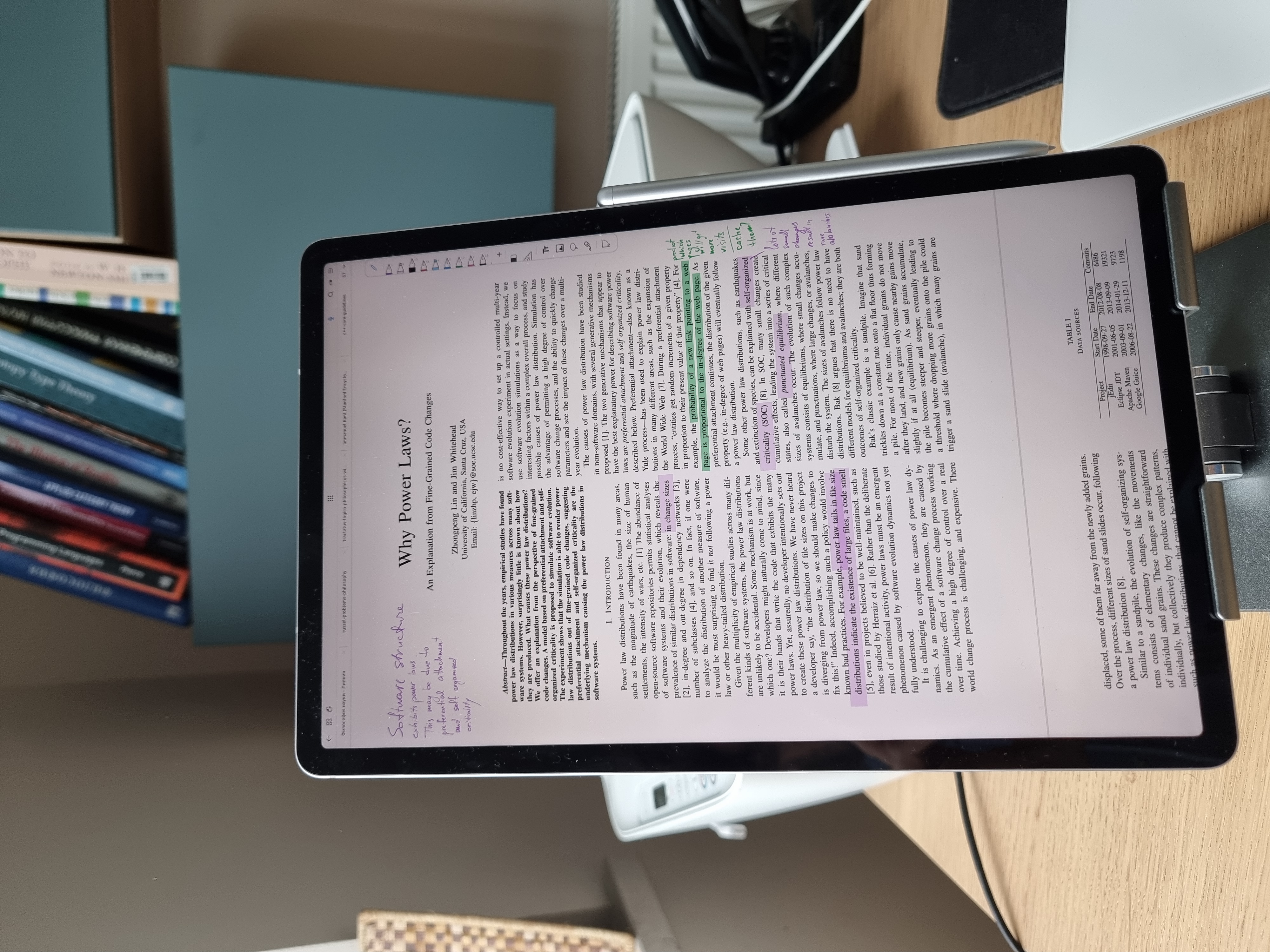

Most of my books or articles are in digital format, so I read a lot on my tablet as well. For that, I have bought Samsung Galaxy Tab7 Fan Edition this summer, and it is just really good for me:

- The screen is big (and I never felt like I have enough screen space for comfortable handwriting before)

- Samsung S-Pen feels good to me, better than Apple pencil. The feel is a bit closer to the fountain pen, which is my writing tool of preference on paper.

- The performance is adequate for everything I need.

As for software, I found that Flexcil works best for me. It does not choke when I open 40 tabs with documents, stays responsive and handles even huge books like Differential geometry reconstructed, which has around 2500 pages as of today.

The editing capabilities are not great, e.g. you can not rotate your handwritten text, and the Android version lacks a good synchronization mechanism – you basically have to do backups and restore them. The backup process is fast thought, so I am just doing backing up my notes in cloud every day. Once these features get implemented, Flexcil will become an ideal tool for me.

I also read for pleasure, without annotating. For that I still prefer using my old e-ink reader PocketBook 902 E-ink displays are easier on my eyes. It has now turned 12 years old, and still works like a charm.

At some point I was considering buying an e-ink tablet for annotating, but I find that having color on annotations is too valuable. The current e-ink tablets were not convincing to me.

Pitfalls

- Do not try to create a hierarchy (taxonomy) for your notes. It is not scalable and only works for narrow domain. Prefer tags.

- I did not perceive this system as too complicated, until I have written this post. Start small, build a habit, grow as you see fit.

- Without a habit, your Zettelkasten will stay empty. You may need to force yourself to stop reading at some point, revise your notes and put them to the permanent database. Do not delay this too much, or you will not be recalling the annotated texts, but rather reading them anew.

- Redundancy is good. You will naturally put the same information in many notes, and it is all right.

- Drawing is great. Emacs and org notes support

.svgfiles, but you can also include photos or screenshots of your hand-drawn diagrams, why not. Think carefully which software you will be using, if any. It is great to have the second brain for life. My first digital notes were in some note-taking app for Symbian OS, then in Evernote. These programs are proprietary and do not always have an easy way for you to migrate your notes somewhere else. Emacs (and text files) is clearly not everyone's darling, but it is free, open-source, and has been around for more, than I am alive. It means that it is flexible enough to adapt to the new technological context: we are not using the same computers with the same operating systems as in 80s anymore, and emacs runs fine on basically everything. I am quite certain that:

- either I will be able to keep my notes there for life,

- or I will be able to migrate them somewhere, should such need arise.

Figure 1: My favorite pen since my teen years is Sheaffer Fashion.

Footnotes:

Most texts are not too dense and include a fair percentage of redundancy, so you can summarize them in a useful way. There are, of course, exceptions, for example, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus of Ludwig Wittgenstein, where the book is a structured tree of key points of his word view from that time. In this case I had to keep the annotations separated from the book.