Impressions of René Magritte

Recently I've been lucky to spend a couple of days in Belgium. I've come to Bruxelles, rushed through Brugge and Gant and ended my journey by visiting René Magritte museum. I was quite impressed, partly because I have not seen much of Magritte before. This post is intended as a quick review of my impressions and thoughts on Magritte style and his philosophy.

First impressions

Magritte's style differs from his fellow surrealists such as Dali or Ernst. I've often got an impression that his approach is quite blunt, a bit like if he threw objects into my face:

- The objects on his pictures are big, take a lot of space on canvas. Moreover, the background is empty and not detailed.

- The palette has usually few colors. Speaking of modern times, it is the same kind of restriction that exists in pixel art, and produces a similar effect on me, that I rather like.

- The colors are rarely bright, which, in conjunction with the previous point, makes paintings look surreal, mystic and alien.

- The shadows and shapes are nicely detailed which makes for a highly contrast image (although you won't see many sharp edges).

The Riddler

Magritte's approach is also quite intellectual because he wants to mess with the viewers and make them think (almost a quote of his). Each pair of a picture and its name is a puzzle to solve. The reward is a better comprehension the message of a picture, which in turn can bring you some new understanding about the real world. The name and the picture can be connected in a number of ways, for example:

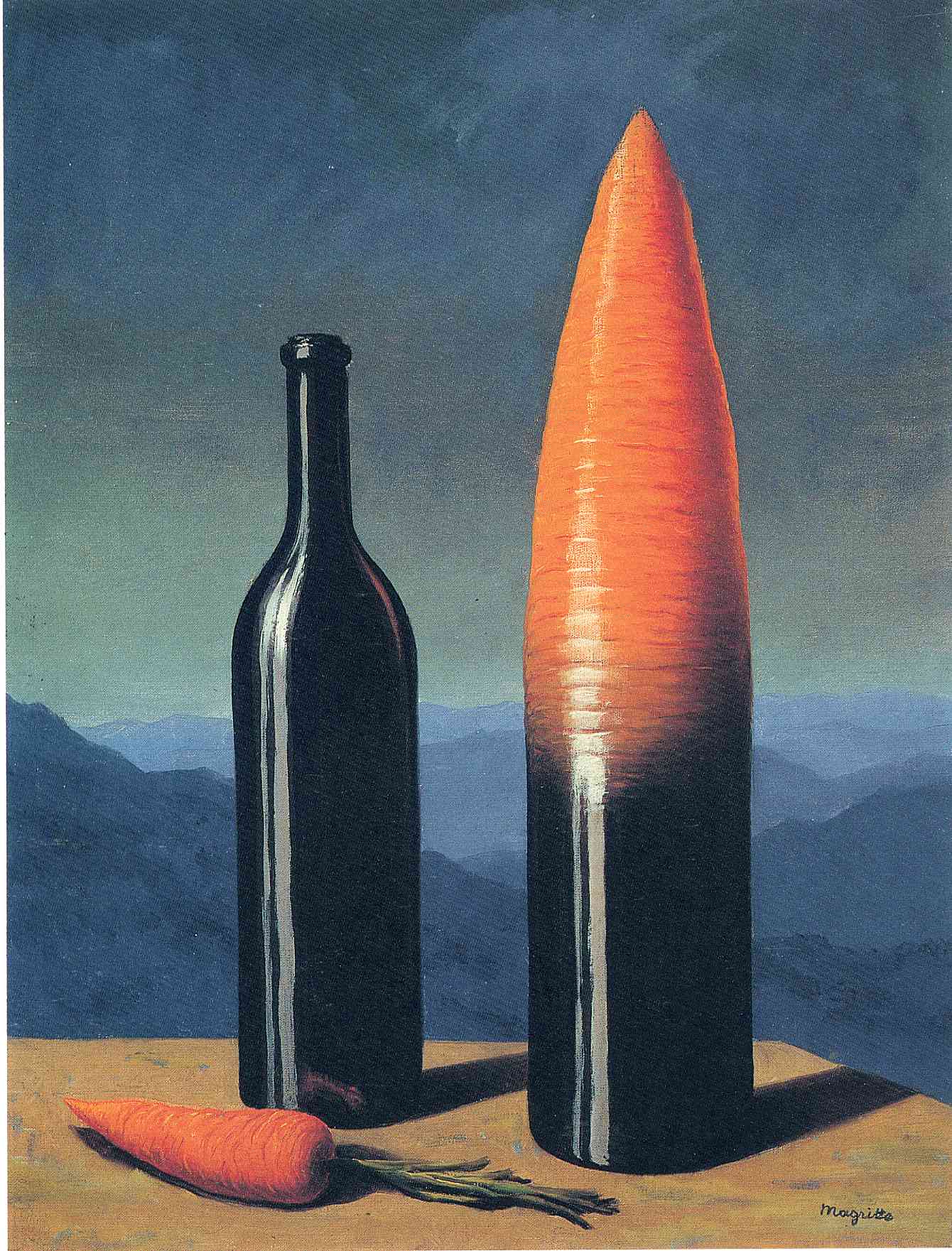

The name can be a hint to solve the riddle. The picture named "Explanation" depicts two bottles, one of which looks like half-bottle, half-carrot. As we see the image and its title, we come to an understanding of what an explanation is, its idea: the explanation is a process of changing our perception and/or understanding of concepts. This change is the transformation of an image of a bottle into an image of a carrot.

The name can be just something vaguely connected to what's on the painting. For example, the name "Imp of the Perverse" should make you think that something wrong is going on, make you uncomfortable, which, in turn, strengthens the feeling of wrongness coming from the piece of art itself. In a sense, Magritte wants you to think critically, not make you trying to connect distantly related terms. We can find a context to associate any pair of words if we want to, though not all contexts are of importance to us.

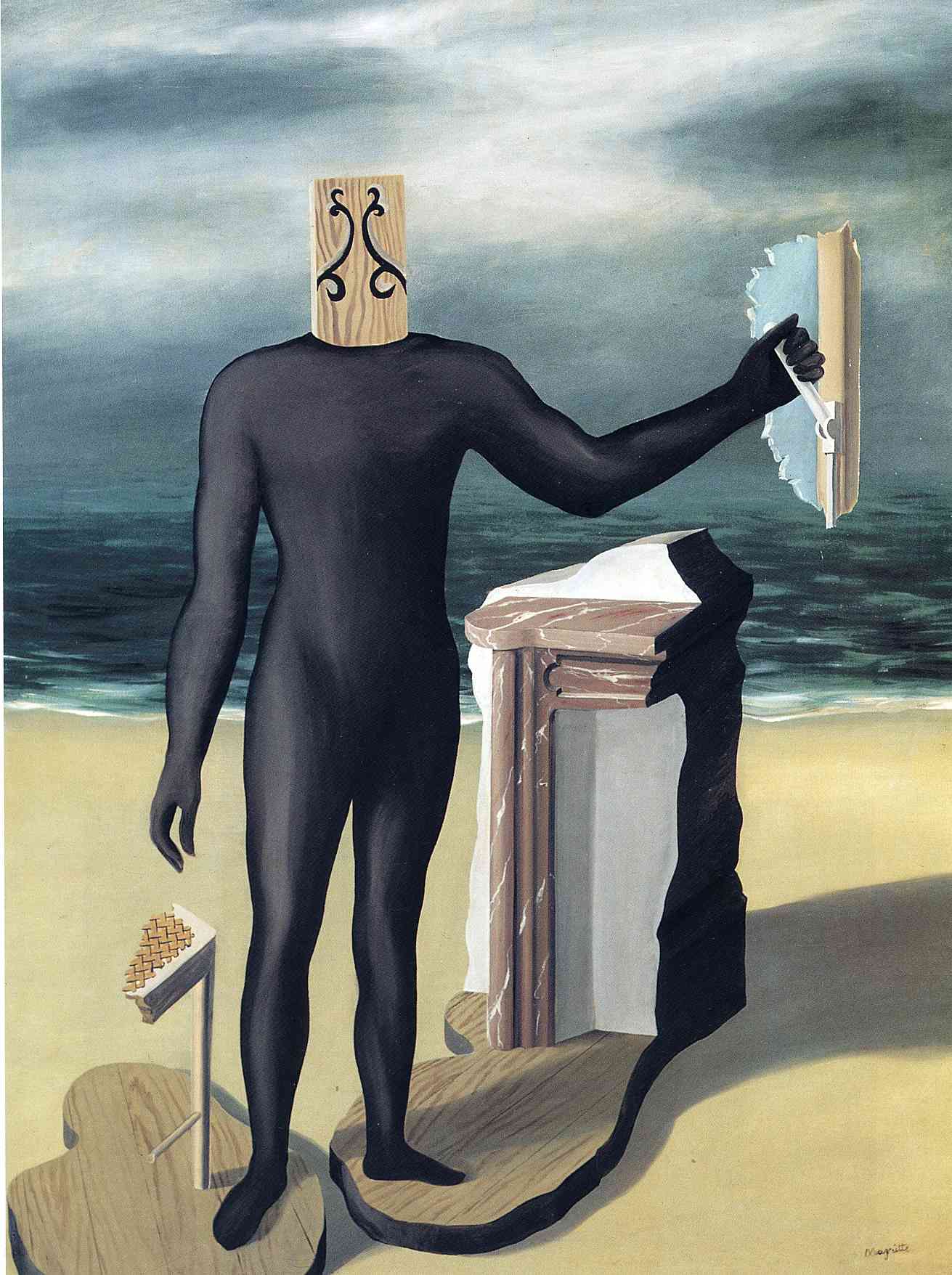

The name might hold an allusion to other works of art Magritte associated his painting with. For example, "The Man from the Sea" refers to the film of Marcel L'Herbier, which tells a story of a lone sailor. More importantly, it resembles the final scene of "Juve against Fantômas" where this villain in black prevails by setting off an explosion with a pull of a lever.

Objects, their images and words

What's especially interesting about Magritte's philosophy is his reflections on images, words and real world objects as well as the relations of the said three worlds. He published his famous text "Words and images" in 1929 in the journal La révolution surréaliste as a result to his extensive experimentation in the late 1920's.

This text studies how words (e.g. poetry) and paintings as the means of expressing ideas. Here is the text in English with a little commentary (it corresponds to the images from up to down, from left to right):

- An object and its name are not inseparable. We can find a better name.

Some objects have no name.

Words are parts of languages, and there is no a language which includes all notions from any other one. Take Dostoevsky's "nadryv" or dozens of words to describe different shades of snow in the local languages of northern tribes. We create names based on our everyday needs and what seems important to us.

A word can be used to refer you to itself.

This thought is illustrated by a word "sky" inside a closed curve, depicting the said sky. As the label "sky" is placed directly on the image of sky, it refers to this exact instance of "sky", which makes for a funny wordplay.

Sometimes a name of an object meets the object depiction.

This is illustrated with a labeled image of a forest.

Sometimes, a name is used in place of an image.

The picture shows a stub silhouette of an object labeled with its name.

- In reality, a word can be used instead of an object.

A word can be substituted by an image.

A pictogram of a sun is used to substitute the word "soleil" (fr. sun).

- An object can suggest that there are other objects behind.

- Everything suggests that there is little common between an object and its representation.

- The words used to represent two objects do not suggest what is different between them.

- On a painting, words are like images.

The images and words are seen in an unusual way when on a canvas.

The illustration shows how a written word "montagne" (fr. mountain) blends in and becomes a part of the object texture.

An arbitrary figure can replace an image of an object.

I am not sure what this means, because the words (labels) are not mentioned. However the illustration has all these random objects labeled as the sun. When the object is labeled (possibly with an unexpected word), that's one thing, but when we deduce that the object is replacing sun just because he is in the context (position, effects etc.) we are used to see the sun in, that's entirely other thing.

The object is never the same thing as its image and/or its name.

I can not stress this enough, as this is quite a useful piece of the puzzle. I will dedicate the next section to this.

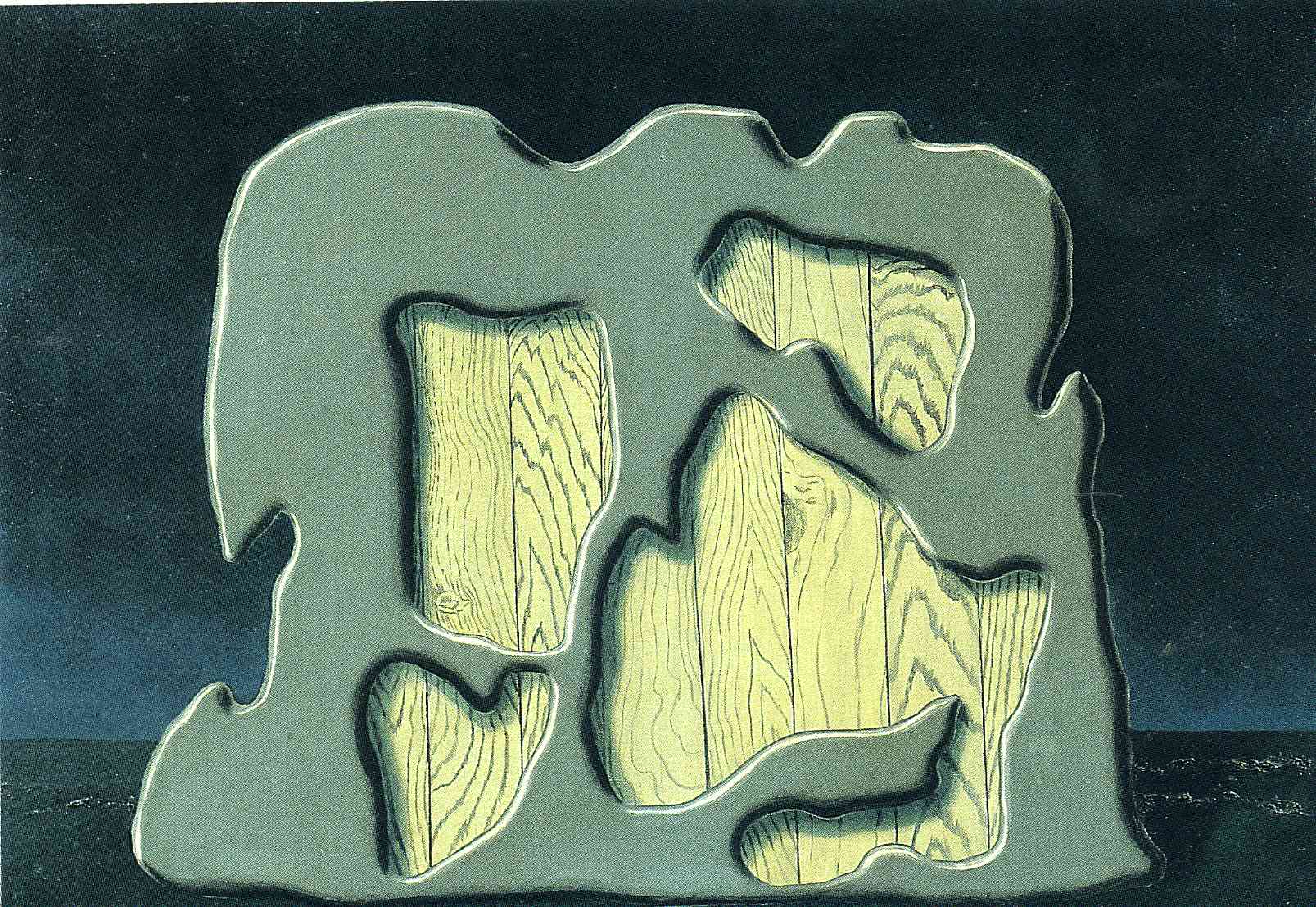

Visible contours of the object form a mosaic in reality.

This is a beautiful thing to notice. I can deduce, that every point of the space can be named based on it being a part of some part of this mosaic.

- The vague shapes have the same significance as the well defined ones.

- Sometimes the labels define precise things, and the images are not.

- Sometimes, it is vice versa.

Images, words and the real world

In this section I want to explore the following thought of Magritte: The object is never the same thing as its image and/or its name.

The real

We are not reasoning about the real world, but about its projection in our head, a kind of a logic system. This is largely used in philosophy, for example, to construct some theories of causation.

We are fundamentally limited like that. It is evident, that our image is only a part of the big picture. So when we reason about real life, we base on the information that could have been warped only once: by our perception. I think, this is also why methods as palpation still hold such an important place in medicine: there are as little between the doctor and the patient as possible.

The image

If we use an image of reality, someone has to create it first – we will call him Creator, and we are his Observers. Where can we get disrupted?

- Creator's perception of reality is not perfect: for example, he can have a mild color blindness; he is also unable to perceive all the infinite details that do exist.

- Creator's way of drawing may be flawed.

- Observer's perception of an image can be flawed.

- Observer's interpretation is flawed.

The word

Words are purer than images in a sense that they represent crystallized ideas. However, the exact meaning of a word can slightly vary because of the differences in cultural background of different people. The existence of dictionaries, however, helps finding a certain common denominator between them, which would be accepted as a norm by most people. We will call the agents Speaker and Listener.

- Speaker can mistake an object for another.

- Speaker can make a bad choice of word.

The word may seem more precise, but it can be ambiguous (multiple meanings in dictionary). Whether it will hold more or less information than an image is debatable and varies from case to case.

It is important to note, that we are only speaking about singular words. They can be ambiguous, but interpreting a word differs from interpreting sentences, which differs from interpretation of texts, which differs from interpretation of texts in specific contexts.

In fact, Magritte's study is about semantics and human interpretation, concentrating especially on human perception of images and words on them. One might say that Magritte was one of pioneers of semiotics in scope of art.