The virtues of using goto

IT folks are prone to prejudices, as we all are. Once a beginner programmer starts exploring the world of coding, he quickly learns catchy memes from the more experienced part of the community. One can then easily live by them without putting much thought in their meaning.

In general, this is also how human society works: we adopt elements of our parents' lifestyle and their world view, we make them parts of ourselves, usually not questioning the reasons for this specific behavior. However, there is one fundamental empirical rule: there are no silver bullets – rules, that are always applicable.

Thus, each of programming memes requires a certain context to be fully

understood. My opinion is that we should always try to reach these deep

foundations in order to understand when the rule can be thrown away for good.

This post is about an absurd meme "goto is bad". We want to explore what

exactly prevents goto from being used well in some contexts and when its use

is quite reasonable.

Why goto is stigmatized in the structured programming

Structured programming is a programming style that (as each style) implies a set of rules and constraints to live by. This style implies an extensive usage of subroutines, loops and code blocks (statement sequences between braces). It usually goes in par with imperativeness, when each programming statement is executed sequentially, and mutable addressable memory – roughly following the von Neumann model of computations. It is safe to say that one of its most devoted supporters was Edsger W. Dijkstra. Object-oriented programming can often be viewed as a slightly tweaked version of it. A large slice of modern programming is structured imperative programming or its variations; moreover, it is what kids are taught in school. Because of that educational system flaw, most of us are deeply infected with an imperative thinking and are often emulating other paradigms on top of it in our heads.

Dijkstra considered goto harmful because it makes harder to follow the code

logic. This is usually true, but needs a clarification. What makes goto

harmful is that it is usually paired with assignments.

Assignments are changing the abstract machine state. When reasoning about a

typical program, we are usually tracing its execution and mark how the values

of the variables are changing. Throwing goto ’s everywhere makes it notably

harder to follow the program state, because you can jump anywhere, from

anywhere. That makes the trace much harder to untangle.

However, throw away the state changes and you will have no problems using multiple goto’s in an isolated piece of code (e.g. inside a particular function), because the interesting state will be determined solely by your current position in code!

Finite State Machines

If we want to implement a Finite State Machine (FSM), then goto ’s are

the way to go! Such an abstract machine consists of:

- a set of states (C labels). One state is marked as an initial state.

- input (sequence of global events, f.e., character input, received network packets, any user actions)

- output (sequence of global actions, responses of the system: send packets or control signals to the connected hardware, output etc.)

- for each state, a set of rules to jump to other states based on the current input.

We start in the initial state and perform jumps between states based on the current input value. As you see, this machine has no memory. If we are implementing them in a language such as C, its state will be characterized solely by the position in the code we are currently at.

Crafting a FSM is equivalent to crafting an algorithm to solve a problem. They are not expressive enough to solve all problems Turing-machines can digest. Nevertheless they are not only potent, but very convenient for some tasks such as template matching in strings, implementing network protocols and robot controlling tasks.

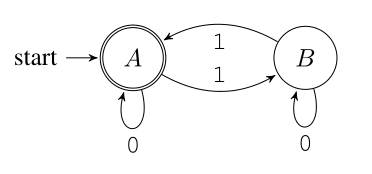

Here is a toy example, taken from [my book](http://www.apress.com/us/book/9781484224021). This FSM checks whether the input string containing only characters 0 and 1 contains an even number of ones. It is common to draw cool looking diagrams for FSM, showing states as circles and transitions as arrows between them.

Let us take a look at its implementation in C. I have omitted error checks for brevity.

#include <stddef.h> #include <stdio.h> /* str should only contain 0 and 1 */ int even_ones( char const* str ) { size_t i = 0; char input; _even: input = str[i++]; if (input == '1') goto _odd; if (input == '0') goto _even; /* end of string -- null terminator */ return 1; _odd: input = str[i++]; if (input == '1') goto _even; if (input == '0') goto _odd; /* end of string -- null terminator */ return 0; } void test( const char* str ) { printf("%s\n", even_ones( str ) ? "yes" : "no" ); } int main(void) { test("0101011"); test(""); test("010"); test("110"); return 0; }

Model checking

An additional benefit is that there exist a quite powerful verification technique called model checking which allows you to reason about the program properties if the said program is encoded as a finite state machine. You can reason about them using temporal logic, checking properties such as "If I got into the state A, I will never reach the state B from there". The model checkers can often generate C program automatically from a FSM description.

For examples of what model checking tools are capable of, I recommend you this exercise page for SPIN model checker.

Deinitializing resources

C++ has a nice feature C lacks. It can automatically call object destructors

whenever the object's lifetime is over. For example, in the following code the

destructor for an object myC will be automatically called after we reach the

closing bracket. But it gets better: every time you are writing a return

statement, everything that exists in the surrent stack frame gets automatically

destroyed in the correct order (reversed initialization order).

Consider this function, which returns the error code and uses three objects:

myA, myB and myC. The respective classes should have defined destructors

which free all associated resources.

#include <iostream> int f() { A myA; B myB; C myC; if (! myA.init() ) return 0; if (! myB.init() ) return 0; // myA's destructor is called if (! myC.init() ) return 0; // myA and myB's destructors are called //... // Destructors for myA, myB, myC will be called here anyway return 1; }

In C we often want to do the same thing, but we do not have that luxury of automatically calling anything. It is, however, very important do to because some structures have dynamically allocated fields or are associated with other resources such as file descriptors. It can easily leak resources. So, to do things right, we have to produce quite a mess:

int f() { struct sa a; struct sb b; struct sc c; if ( ! sa_init( &a ) ) return 0; if ( ! sb_init( &b ) ) { sa_deinit( &a ); return 0; } if ( ! sc_init( &c ) ) { sb_deinit( &b ); sa_deinit( &a ); return 0; } return 1; }

Imagine you had 5 structures to work with, this straightforward approach is

going to turn your code into nightmare! However, with the help of goto's we

are going to exploit a nice little trick. It bases on the fact that all such

branches can be ordered by inclusion: each branch looks exactly like some

other branch preceded by an additional deinit:

// return 0; sa_deinit( &a ); return 0; sb_deinit( &b ); sa_deinit( &a ); return 0;

If we throw labels in between we could jump to any statement in this sequence. Then all following statements will be executed as well. This way we are going to refactor the example above to look like this:

// int f() { struct sa a; struct sb b; struct sc c; if ( ! sa_init( &a ) ) goto fail; if ( ! sb_init( &b ) ) goto fail_b; if ( ! sc_init( &c ) ) goto fail_c; return 1; fail_c: sb_deinit( &b ); fail_b: sa_deinit( &a ); fail: return 0; }

Isn't it way nicer that what we have seen before? Additionally, no assignments

are performed hence no fuss about goto evilness at all.

Computed goto

Computed goto is a non-standard feature supported by many popular C and C++

compilers. Basically, it allows to store a label into a variable and perform

jumps to it. It differs from calling function by pointer because no return is

ever performed. The simplest case is shown below:

#include <stdio.h> int main() { void* jumpto = &&label; goto *jumpto; puts("Did not jump"); return 0; label: puts("Did jump"); return 1; }

We are taking raw label address using an unusual double ampersand syntax and

then perform a goto. Notice the additional asterisk before goto

operand. When launched, this program will output Did jump.

Where can we use such a feature? Expressivity wise, it is not very interesting.

However, sometimes we can get a speedup. A case that comes to my mind is a

bytecode interpreter (but I have written hell of a ton of them, so I should be

quite biased towards them). The instruction fetching takes typically no less

than 30% of the execution time, and computed goto allows one to speed it up.

Without computed goto:

#include <stdio.h> #include <inttypes.h> enum bc { BC_PUSH, BC_PRINT, BC_ADD, BC_HALT }; uint8_t program[] = { BC_PUSH, 1, BC_PUSH, 41, BC_ADD, BC_PRINT, BC_HALT }; void interpreter( uint8_t* instr ) { uint8_t stack[256]; uint8_t* sp = stack; for (;;) switch ( *instr ) { case BC_PUSH: instr++; sp++; *sp = *instr; instr++; break; case BC_PRINT: printf( "%" PRId8 "\n", sp[0] ); instr++; break; case BC_ADD: sp--; sp[0] += sp[1]; instr++; break; case BC_HALT: return; } } int main() { interpreter( program ); return 0; }

With computed gotos:

#include <stdio.h> #include <inttypes.h> enum bc { BC_PUSH, BC_PRINT, BC_ADD, BC_HALT }; uint8_t program[] = { BC_PUSH, 1, BC_PUSH, 41, BC_ADD, BC_PRINT, BC_HALT }; void interpreter( uint8_t* instr ) { uint8_t stack[256]; uint8_t* sp = stack; void* labels[] = { &&label_PUSH, &&label_PRINT, &&label_ADD, &&label_HALT }; goto *labels[*instr]; label_PUSH: instr++; sp++; *sp = *instr; instr++; goto *labels[*instr]; label_PRINT: printf( "%" PRId8 "\n", sp[0] ); instr++; goto *labels[*instr]; label_ADD: sp--; sp[0] += sp[1]; instr++; goto *labels[*instr]; label_HALT: return; } int main() { interpreter( program ); return 0; }

We replaced switch with an array storing the address of an instruction

handler. Each time we fetch an instruction, we are using its bytecode as an

offset in this array. After taking an address from there, we jump to it. The

larger the instruction set and the switch gets, the more noticeable gets the

difference in a real world program.

Using switch slow us down for two reasons:

- It is forced to perform the bounds check according to C standard. If no

caseexists for aswitchexpression, and thedefaultcase is missing as well, no part of theswitchbody is executed1. Computedgotowill just result in an undefined behavior in case of an invalid opcode. - When using

switch, there is a single point where the decision about where are we going is taken. In case of computedgoto, such decisions are taken at the end of each instruction handler. It makes CPU hold separate prediction histories for each decision making point, which is good for dynamic branch-predicting algorithms.

Starting with Haswell architecture the branch prediction algorithms were tuned

so that switch is predicted better, so the performance gain from using

computed goto is not that substantial.

P.S. If you really want to make a faster interpreter, consider implementing

indirect threaded code, direct threaded code or write a JIT compiler.

Computed goto is not a magical thing to make your interpreter as fast as

possible.

Footnotes:

C99 standard, Section 6.8.4.2.